Biographies

Sean: how can students be agents of their own learning?

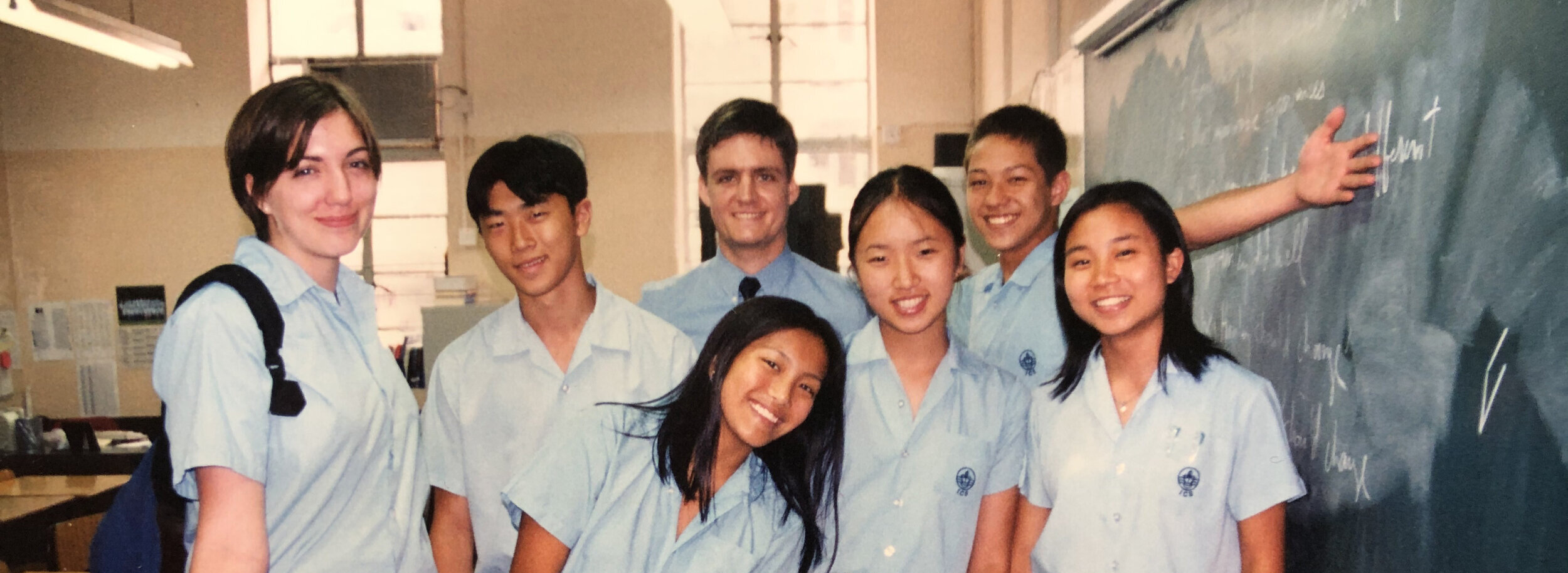

I began my work in education as an idealistic young English teacher at a wonderful school in Hong Kong called International Christian School. I quickly realized that students came to my classes not as blank slates, but as thoughtful people with big, urgent questions about life. Given the opportunity to explore those questions through the study of literature, students would propel the learning process in profound directions. I tried to create as much space as possible for what I later called “student agency,” and encountered various ways that the larger structures of the school could facilitate, or inhibit, that work. After many conversations with colleagues about what our “dream school” would look like, I engaged in graduate studies at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in order to explore how a school might be designed to cultivate student agency.

Later, at Eagle Hill School, a boarding school in central Massachusetts, I began to implement that ideal as the founding director of the Cultural Center at Eagle Hill, a performing arts center integrating full seasons of public programming, galleries, student internships, and artist residencies, all of which helped to connect the lives of students and adult professionals in meaningful ways by inviting students to help shape this undertaking, engaging in work of great value to the larger community.

My past nine years in Christian education since then – as a teacher, dean, principal, and head of school – have been a joyous, excruciating, painful, frustrating process of delicately re-engineering traditional school structures in order to create space for students to chart a course and discover their callings.

But schools resist change -- even change that constituents agree is good; and Christian schools are even more resistant to change than their secular counterparts. So, I am starting from scratch -- working with like-minded colleagues on a new kind of school that is designed for flexibility and sustainability; that is designed around what is known about how kids learn; that is designed to let students help chart their educational journeys; that is designed to cultivate an authentic community of faith.

Shannon: how can a school be a force for justice and goodness?

My first job out of college was with the Migrant Education Program, serving students from migrant families through after school tutoring and summer school. In that space I worked alongside brilliant, multi-lingual students who were too often taken for granted by a system that saw them as liabilities, threats to the district standardized testing average. And yet these same students lived the challenge of having to balance the role of adult and child as they translated for their parents in a variety of community settings.

I became a teacher after two years of working with the Migrant Education Program in Pennsylvania. Yet it was motherhood that finally and firmly hooked me on education as my calling nearly a decade later. I saw through my children’s eyes that learning is not always fun, that who they are as humans is not always honored in a traditional classroom setting. Traditional schooling truly serves a very small segment of our population. All students are capable of learning, and all students can and should feel successful when they are in school. Being a student could mean endless exploration, asking great questions and actively pursuing them to interesting and novel conclusions. Instead, the life of a student seems an onerous drudge.

Something needs to change. While I believe in education, I am not convinced that our current system is capable of the reforms necessary to truly bring about change that students will feel experientially. I agree with Gloria Ladson-Billings (2006) that we are beyond our ability to climb out of the debt that we owe to our underserved students. Perhaps what we most need is to declare bankruptcy and start over. In a small yet profound way, co-founding the New Christian School feels like an opportunity to start over, especially on behalf of students who have traditionally been underserved by our educational systems. It is an opportunity to seek repentance for the thousands of Christian schools that have been complicit in white supremacy as exclusive institutions that have proved unwelcoming to people, thoughts and ideas that do not match those of the dominant culture.

My hope is that the New Christian School will represent ideas and ways of learning and being which will transform students into active citizens who love mercy, seek justice and walk humbly before God.